Clinical

Examination of the Chest

As medical personnel, you will be examining the chest to

detect evidence of disease. Your examination consists of inspection, palpation,

percussion, and auscultation

Inspection

shows the configuration of the chest, the range of respiratory movement, and any inequalities on the two sides. The type and rate of respiration are also noted.

shows the configuration of the chest, the range of respiratory movement, and any inequalities on the two sides. The type and rate of respiration are also noted.

Palpation

enables the physician to confirm the impressions gained by inspection, especially of the respiratory movements of the chest wall. Abnormal protuberances or recession of part of the chest wall is noted. Abnormal pulsations are felt and tender areas detected.

enables the physician to confirm the impressions gained by inspection, especially of the respiratory movements of the chest wall. Abnormal protuberances or recession of part of the chest wall is noted. Abnormal pulsations are felt and tender areas detected.

Percussion

is a sharp tapping of the chest wall with the fingers. This produces vibrations that extend through the tissues of the thorax. Air-containing organs such as the lungs produce a resonant note; conversely, a more solid viscus such as the heart produces a dull note. With practice, it is possible to distinguish the lungs from the heart or liver by percussion.

is a sharp tapping of the chest wall with the fingers. This produces vibrations that extend through the tissues of the thorax. Air-containing organs such as the lungs produce a resonant note; conversely, a more solid viscus such as the heart produces a dull note. With practice, it is possible to distinguish the lungs from the heart or liver by percussion.

Auscultation

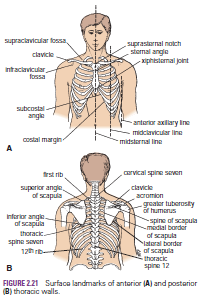

enables the physician to listen to the breath sounds as the air enters and leaves the respiratory passages. Should the alveoli or bronchi be diseased and filled with fluid, the nature of the breath sounds will be altered. The rate and rhythm of the heart can be confirmed by auscultation, and the various sounds produced by the heart and its valves during the different phases of the cardiac cycle can be heard. It may be possible to detect friction sounds produced by the rubbing together of diseased layers of pleura or pericardium. To make these examinations, the physician must be familiar with the normal structure of the thorax and must have a mental image of the normal position of the lungs and heart in relation to identifiable surface landmarks. Furthermore, it is essential that the physician be able to relate any abnormal findings to easily identifiable bony landmarks so that he or she can accurately record and communicate them to colleagues. Since the thoracic wall actively participates in the movements of respiration, many bony landmarks change their levels with each phase of respiration. In practice, to simplify matters, the levels given are those usually found at about midway between full inspiration and full expiration.

enables the physician to listen to the breath sounds as the air enters and leaves the respiratory passages. Should the alveoli or bronchi be diseased and filled with fluid, the nature of the breath sounds will be altered. The rate and rhythm of the heart can be confirmed by auscultation, and the various sounds produced by the heart and its valves during the different phases of the cardiac cycle can be heard. It may be possible to detect friction sounds produced by the rubbing together of diseased layers of pleura or pericardium. To make these examinations, the physician must be familiar with the normal structure of the thorax and must have a mental image of the normal position of the lungs and heart in relation to identifiable surface landmarks. Furthermore, it is essential that the physician be able to relate any abnormal findings to easily identifiable bony landmarks so that he or she can accurately record and communicate them to colleagues. Since the thoracic wall actively participates in the movements of respiration, many bony landmarks change their levels with each phase of respiration. In practice, to simplify matters, the levels given are those usually found at about midway between full inspiration and full expiration.