Breast

Examination

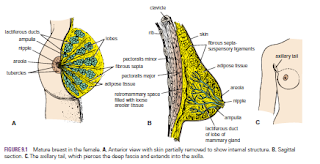

Because The breast is

one of the common sites of cancer in women. It is also the site of different

types of benign tumors and may be subject to acute inflammation and abscess

formation. For these reasons, the clinical personnel must be familiar with the

development, structure, and lymph drainage of this organ.

With the patient undressed to the waist and sitting upright,

the breasts are first inspected for symmetry. Some degree of asymmetry is

common and is the result of unequal breast development. Any swelling should be

noted. A swelling can be caused by an underlying tumor, a cyst, or abscess

formation. The nipples should be carefully examined for evidence of retraction.

A carcinoma within the breast substance can cause retraction of the nipple by

pulling on the lactiferous ducts. The patient is then asked to lie down so that

the breasts can be palpated against the underlying thoracic wall. Finally, the

patient is asked to sit up again and raise both arms above her head. With this

maneuver, a carcinoma tethered to the skin, the suspensory ligaments, or the

lactiferous ducts produces dimpling of the skin or retraction of the nipple.

Mammography

Mammography is a radiographic examination of the breast.

This technique is extensively used for screening the breasts for benign and

malignant tumors and cysts. Extremely low doses of x-rays are used so that the

dangers are minimal, and the examination can be repeated often. Its success is

based on the fact that a lesion measuring only a few millimeters in diameter can

be detected long before it is felt by clinical examination.

Breast

Abscess

during lactation An acute infection of the mammary gland may

occur. Pathogenic bacteria gain entrance to the breast tissue through a crack

in the nipple. Because of the presence of the fibrous septa, the infection

remains localized to one compartment or lobe to begin with. Abscesses should be

drained through a radial incision to avoid spreading of the infection into neighboring

compartments; a radial incision also minimizes the damage to the radially

arranged ducts.

Lymph

Drainage and Carcinoma of the Breast

The importance of knowing the lymph drainage of the breast

in relation to the spread of cancer from that organ cannot be overemphasized. The

lymph vessels from the medial quadrants of the breast pierce the 2nd, 3rd, and

4th intercostal spaces and enter the thorax to drain into the lymph nodes

alongside the internal thoracic artery. The lymph vessels from the lateral

quadrants of the breast drain into the anterior or pectoral group of axillary nodes.

It follows, therefore, that a cancer occurring in the lateral quadrants of the

breast tends to spread to the axillary nodes.

Thoracic metastases are difficult or impossible to treat,

but the lymph nodes of the axilla can be removed surgically. Approximately 60%

of carcinomas of the breast occur in the upper lateral quadrant. The lymphatic

spread of cancer to the opposite breast, to the abdominal cavity, or into lymph

nodes in the root of the neck is caused by obstruction of the normal lymphatic

pathways by malignant cells or destruction of lymph vessels by surgery or

radiotherapy. The cancer cells are swept along the lymph vessels and follow the

lymph stream. The entrance of cancer cells into the blood vessels accounts for

the metastases in distant bones.

In patients with localized cancer of the breast, most

surgeons do a simple mastectomy or a lumpectomy, followed by radiotherapy to

the axillary lymph nodes and/or hormone therapy. In patients with localized cancer

of the breast with early metastases in the axillary lymph nodes, most

authorities agree that radical mastectomy offers the best chance of cure. In

patients in whom the disease has already spread beyond these areas (e.g., into

the thorax), simple mastectomy, followed by radiotherapy or hormone therapy, is

the treatment of choice. Radical mastectomy is designed to remove the primary

tumor and the lymph vessels and nodes that drain the area. This means that the

breast and the associated structures containing the lymph vessels and nodes

must be removed en bloc. The excised mass is therefore made up of the

following: a large area of skin overlying the tumor and including the nipple;

all the breast tissue; the pectoralis major and associated fascia through which

the lymph vessels pass to the internal thoracic nodes; the pectoralis minor and

associated fascia related to the lymph vessels passing to the axilla; all the

fat, fascia, and lymph nodes in the axilla; and the fascia covering the upper

part of the rectus sheath, the serratus anterior, the subscapularis, and the

latissimus dorsi muscles. The axillary blood vessels, the brachial plexus, and

the nerves to the serratus anterior and the latissimus dorsi are preserved.

Some degree of postoperative edema of the arm is likely to follow such a

radical removal of the lymph vessels draining the upper limb. A modified form

of radical mastectomy for patients with clinically localized cancer is also a

common procedure and consists of a simple mastectomy in which the pectoral

muscles are left intact. The axillary lymph nodes, fat, and fascia are removed.

This procedure removes the primary tumor and permits pathologic examination of

the lymph nodes for possible metastases

Carcinoma

in the Male Breast

Carcinoma in the male breast accounts for about 1% of all

carcinomas of the breast. This fact tends to be overlooked when examining the

male patient.

Since the amount of breast tissue in the male is small, the tumor

can usually be felt with the flat of the examining hand in the early stages.

However, the prognosis is relatively poor in the male, because the carcinoma

cells can rapidly metastasize into the thorax through the small amount of

intervening tissue.