Brachial

Plexus

The nerves entering the upper limb provide the following

important functions: sensory innervation to the skin and deep structures, such

as the joints; motor innervation to the muscles; influence over the diameters

of the blood vessels by the sympathetic vasomotor nerves; and sympathetic

secretomotor supply to the sweat glands. At the root of the neck, the nerves

form a complicated plexus called the brachial plexus. This allows the

nerve fibers derived from different segments of the spinal cord to be arranged

and distributed efficiently in different nerve trunks to the various parts of

the upper limb. The brachial plexus is formed in the posterior triangle of the

neck by the union of the anterior rami of the 5th, 6th, 7th, and 8th cervical and

the 1st thoracic spinal nerves.

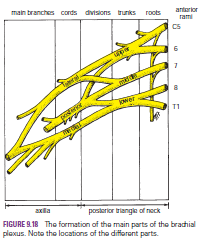

The plexus can be divided into roots, trunks, divisions,

and cords. The roots of C5 and 6 unite to form the upper trunk, the

root of C7 continues as the middle trunk, and the roots of C8 and T1

unite to form the lower trunk. Each trunk then divides into anterior and

posterior divisions. The anterior divisions of the upper and middle trunks

unite to form the lateral cord, the anterior division of the lower trunk

continues as the medial cord, and the posterior divisions of all three

trunks join to form the posterior cord.

The roots, trunks, and divisions of the brachial plexus

reside in the lower part of the posterior triangle of the neck and are fully

described on page XXX. The cords become arranged around the axillary artery in

the axilla. Here, the brachial plexus and the axillary artery and vein are

enclosed in the axillary sheath.

Cords of the Brachial Plexus All three cords of the

brachial plexus lie above and lateral to the first part of the axillary artery.

The medial cord crosses behind the artery to reach the medial side of the second

part of the artery . The posterior cord lies behind the second part of the

artery, and the lateral cord lies on the lateral side of the second part of the

artery . Thus, the cords of the plexus have the relationship to the second part

of the axillary artery that is indicated by their names.

Most branches of the cords that form the main nerve trunks

of the upper limb continue this relationship to the artery in its third part .

The branches of the different parts of the brachial

plexus are as follows:

■■ Roots

Dorsal scapular nerve (C5)

Long thoracic nerve (C5, 6, and 7)

■■ Upper

trunk

Nerve to subclavius (C5 and 6)

Suprascapular nerve (supplies the supraspinatus and

infraspinatus muscles)

■■ Lateral

cord

Lateral pectoral nerve

Musculocutaneous nerve

Lateral root of median nerve

■■ Medial

cord

Medial pectoral nerve

Medial cutaneous nerve of arm and medial cutaneous

nerve of forearm

Ulnar nerve

Medial root of median nerve

■■ Posterior

cord

Upper and lower subscapular nerves

Thoracodorsal nerve

Axillary nerve

The

Axillary Sheath and a Brachial Plexus Nerve Block

Because the axillary sheath encloses the axillary vessels

and the brachial plexus, a brachial plexus nerve block can easily be obtained.

The distal part of the sheath is closed with finger pressure, and a syringe

needle is inserted into the proximal part of the sheath. The anesthetic

solution is then injected into the sheath, and the solution is massaged along the

sheath to produce the nerve block. The position of the sheath can be verified by

feeling the pulsations of the third part of the axillary artery.